The 1990s, Adventures in Becoming Myself by Cheryl Downes McCoy

Dancing for Plane Fare

When the 90s began, I was wrapping up a year of cocktail waitressing and dancing on the tables at a beach-themed nightclub in a suburban strip mall in Wisconsin. We wore open Hawaiian shirts over bikini tops with shorts, and (on weekends) sold premixed cocktails, called Blowjobs and Tequilla Poppers, from the bottle holsters on our hips and shot glasses loaded into a bandolier across our chests. When the DJ, high up in the booth over the dancefloor, hit the siren, we’d put down our trays, hop up on a bar or table and dance a choreographed routine to one of the chosen songs. I still do it in my head, when I hear Salt N’ Pepa’s “Push it Real Good.”

I’d gotten this gig after graduating from U.C. Berkeley with a dilettante’s degree in Religions Studies. I had zero job prospects and a burning desire to see the world. To earn the money to make that happen, I accepted my parents’ generous offer to live rent-free with them for a year in their new home Wisconsin. This was a place where I knew no one, so I wouldn’t have a social life, and would be able save every quarter towards my goal.

Come March of 1990, having saved enough to purchase a ‘round-the-world ticket, and made notes in an excessive number of Lonely Planet Guides, I set out on a 10-month, solo adventure. I hit a few highlights in Western Europe, spent some time clearing bottles from a bar on Corfu Greece in exchange for room and board, then travelled through the recently opened (and ill-equipped for travelers,) countries of Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary. On to Southeast Asia, where I stumbled awed and wide-eyed throughout my time in Northern India, Nepal, Thailand, and Indonesia.

On the wall above Dubrovnik in what was still Yugoslavia

Riding a tiny, rented motorcycle above the rice fields in the foothills of the Himalayas

It was an epic, once in lifetime experience, that opened my mind and heart, and taught me about the beautiful, painful, complex oneness of humankind. I carried a backpack, a plane ticket, a money pouch inside my clothes (containing my passport, US dollars, and some traveler’s checks,) my curiosity, and a sense of fearlessness that only the stupidity of youth and privilege can provide.

Boston Rock & Science Docs

When I returned to the states, I settled in Boston, landing first with an old college friend, then on to a large, dirt-cheep, art-filled, crash pad of a house in Allston, with no front door lock, a rotating cast of roommates, and a salvaged mail-truck with no seats parked out the front, that our roommate used for moving his sculptures and driving the free-rolling pile of us around to shows. I collected a wildly creative group of friends, mostly musicians, who I would come to feel like college buddies without the college.

In the beginning, I worked at a used bookstore during the day and cocktail waitressed at a club, a few nights a week. Whenever I wasn’t working, I saw/heard live music. This was Boston in the early 90s! I was one of few non-musicians, and I went to every show I could. Everyone I knew was in some nascent punk, grunge, power-pop, funk, metal, industrial, Indie band with an incestuously changing lineup.

Boston frolickers frolicking

At work, I met the folks who would help me get a foot in the door as an intern working on a PBS documentary series, which led to a position at a production company, run by the creators of NOVA. I worked on pop-science documentaries and episodes of Scientific American Frontiers for PBS. Suddenly it seemed I had a real job, which was something none of my friends had. I was in my twenties. I got a decent paycheck and had no responsibilities.

I called my job “legitimized curiosity” because I was allowed to experience things that only the possession of a professional-looking camera permits (like, standing in the operating room during open-heart surgery, flying a room-sized hydraulic flight simulator, and riding along with the NYPD on calls.)

Once I had the means, I moved out of the party house. I eventually got my own tiny studio on the top floor of a once fancy hotel near Symphony Hall, that had become a rundown apartment building. The bathroom (nearly the size of the rest of the apartment) had a huge clawfoot tub, whose toenails I painted red, and marble walls. The building had a convenience store on the first floor, a cast of residents that belonged in a Jarmusch film, and a Super who was sent to jail for life, for selling a shit-ton of heroin out of his apartment and continuing to cash the Social Security checks of an elderly resident long after she died.

For me, this was a time of unfettered freedom. I had the best job in the world and whenever I was home from our shoots, I rode my yellow bicycle to all the bars and shows. I wore short skirts, black leggings, and a leather jacket. I had a single key to my apartment on a string around my neck. I tucked cash and my ID into the top if my combat boots.

A Bizarre New Bay Area

After a couple brutal winters, I decided I was done with the snow, bought a friends 1977 Chevy Malibu for $200, attached a U-Haul and drove with a friend (who quickly became a lover) back to the West Coast. I was determined to live in San Francisco—not Berkeley—this time. While I had loved going to college in Berkeley, the carefree, Grateful Dead follower hippy vibe that had welcomed me in the 1980s had evolved into a junkie, scammer, dirtbag, scene from which I wanted to distance myself.

My 1977 Chevy Malibu got 9MPG. It’s open door took up a whole parking space.

I arrived in SF with the momentum and connections to land one last PBS series, on the history of person computers (called “Triumph of the Nerds”.) While working on the series we met and interviewed the inventers, garage tinkerers, founders, pioneers, and early employees of all the technology companies you’ve heard of. I have stories about Jobs and Woz, Gates, Allen, Ellison, and dozens more you’ve never heard of.

After the show aired, there were tumbleweeds on the job front for a while. I scraped by and eventually talked myself into a job at the nascent Wired Digital (then called Hotwired) despite having no relevant experience or even an aptitude for the WWW. Name-dropping the folks I’d met on Nerds, and the fact that no one else knew what they were doing, provided a foot in the door. They gave me a job where I wasn’t going to cause too much trouble and a title I didn’t deserve (Associate Managing Editor of Wired News,) and I officially joined the crazy pre-dot com Web world.

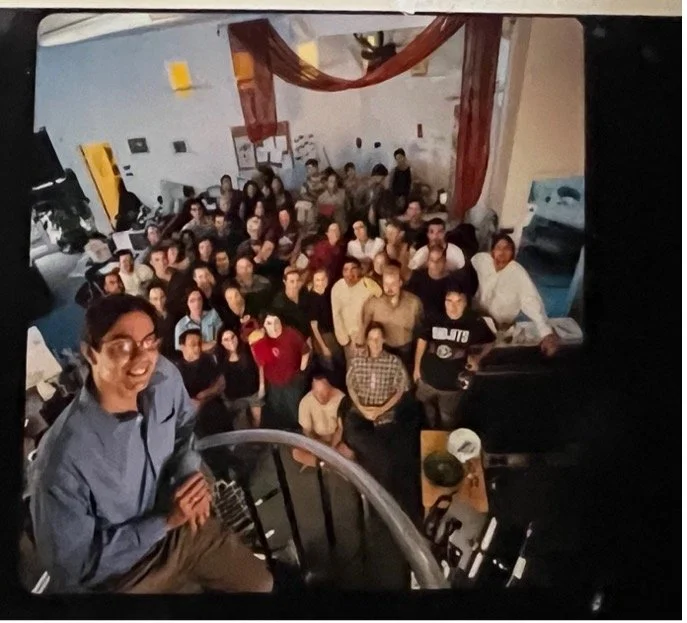

Inside our offices at Hotwired, images from Janelle Brown

I left Wired before my stock vested (because I didn’t understand what it was) for a job as a Producer (I knew how to manage people and projects!) at an early Web shop called Vivid Studios (not the porn site.) They started me at an insane $75K, which would rise to $125K before a year was out, because every time we hired a new producer the rest of us were brought up to parity.

Vivid was next door to Wired, downstairs from Organic, and across the street from South Park and Caffe Centro where I got my near-daily, Salade Niçoise and all the interweb hipsters lounged on the lawn. My co-workers became my best friends and my entire social life (in no small part due to the sheer number of hours we spent together.) Work and parties and sex and drugs and our belief in the vast unifying potential of the work we were doing connected us in such significant ways that I am still close and in regularly in touch with the folks I met back then.

My “professional headshot” for Vivid Studios

Halloween in the mid-90s

Headlong into Living

I lived first in Noe Valley, and then on Duboce Triangle Park, and when my boyfriend and I broke up, I got myself a tiny studio on the corner of Gough and Hayes. The undeveloped Hayes Valley had one brand-new restaurant, called Absinthe, and a single, too expensive shoe store.

By 1997, I’d signed on with an honest to goodness start-up, called BigStep.com, for even more money and more responsibility. I was 31 and on my first day of work, the head of engineering said, “It’s so nice to have an adult on staff, now.” There were fewer than twenty of us at the start, and I would ride this first of its kind, Build-Your-Own Business Website company through to the end of the decade, at which point I was the Executive Producer of an impressive Internet business with over three-hundred employees.

It was such a cool idea! We thought we were the good guys helping all the independent small businesses create their own online stores. And we meant to be. But then we grew and expanded from our cramped space in a janky Mission/Potrero condo into a big building on Mission Street, where we were quickly “occupied” by a bunch of black-clad, bandana-masked white punks our age, who marched into our room full of bicycles, and dogs, and computers propped on shared hollow core doors, chanting in their college Spanish about how we were gentrifiers ruining the neighborhood. Maybe we were.

Throughout this time, I rode a sparkle-red 70’s vintage Honda motorcycle. I wore soft leather pants and faux fur. I haunted the thrift shops and hip boutiques. I came and went on my own, meeting friends at Doc’s Clock or Zeitgeist, or any of the new bars popping up by the minute. I ate out every night. I spent insane amounts of money at Slow Club after a long day of work, and had a weekly date at Delfina, with my old college roommate, who knew the owner. I learned about wine and who makes the best panna cotta. I never considered that the money might run out.

Early days at BigStep.com, we were featured in a bunch of mags

My social circle continued to be made up of the folks I worked with nights and days and weekends because of versions, and Betas, and launches, and machines that texted people day and night. In the hours I wasn’t working or eating and drinking my way across the city, I took painting classes with a favorite teacher at the Art Institute in North Beach, and yoga classes with a Romanian ex-circus performer in the relatively undiscovered Potrero neighborhood. I paid for my first expensive-but-worth-it haircuts and dye jobs at a salon in the Castro (a friend told me my hair color looked like “aqueous wood.”) I bought myself anthropomorphic taxidermy scenes and flirted with the staff at Paxton Gate. I hit on the lesbians at The Lex. I stayed out late, slept with whoever I wanted, drank more than was good for me, and saw live music on the occasions when my Boston friends came to town. One birthday, I rented out the art gallery and bar, 111 Minna, ordered Middle Eastern food delivered, and invited every single person I knew to come celebrate.

Burning Man late 90s. Polaroids were my medium of choice.

Entering the Chrysalis Stage

By 1999, the writing was on the wall, our funders decided they couldn’t wait until we were booking revenue (per our five-year business plan) and pulled their millions. We folded as the decade ended, in small waves of excruciating layoffs, but with at least enough grace to grant some severance to each.

In the last months before Y2K brought the 90s to its ridiculous end, I met my ex-husband-to-be at a launch party for some long-forgotten website, built by an equally insignificant design studio. The marriage that I thought was the start of something exciting and new turned out (in retrospect) to be the beginning of a period of contraction and compromise, of bending to fit, and giving up on confidence, and spontaneity, and freedom. In the years that followed, while I’d find another cool new career, and have a child who would become the focus of all my love and energy—the person who was me largely disappeared.

This Very Hungry Caterpillar of the 1990’s entered a twenty-five-year chrysalis stage. I think I dissolved into a stew of potential (scientific term, “imaginal discs”) and took a good long while to re-form. It’s only now, in 2025, that I feel ready for an older, wiser (albeit achier) winged beauty to emerge. Perhaps, now barely sixty, the same stuff that comprised the cocktail waitress who saved every tip to circumnavigate the globe has reorganized itself into something wholly and gloriously new. Becoming oneself can take a while. But just this year, my divorce is final, my house of 21-years has been sold, my chaplaincy school is in the bag, and I’ve been ordained as a Spiritual Caregiver & Interfaith Chaplain. Maybe I am like a butterfly. Or maybe, I’m like an old car that was cool in the 90s, garaged for two decades, and is finally restored and back on the road.

Today, with a nod to the 1990s, I’m setting up my new apartment, I’m putting on the Pixies, and I’m looking for a date.

Cheryl Downes McCoy is a poet, chaplain, mother, and all-around badass friend. Two books of poetry, Strong Back, Soft Front, and The Thing About Feathers, can be found here and here. Choosing to Love, a KQED Perspectives piece, can be found here.