One Way Ticket by Julie Kramer

I was a good girl. Straight A’s at a well-respected college back East. A virgin. No drinking or drugs except the occasional inhale of a joint offered by my older siblings.

I needed to get the fuck out of Massachusetts and find out who I really was.

The choice was simple: after graduation, I packed my things in a few boxes and shipped them to Oakland. My big sister lived there and would share her home with me for a month, while I looked for work. The next month I had a house-sitting job in Noe Valley, for a lesbian couple my aunt knew.

The job I found was also in Noe Valley: managing one of a chain of bougie food stores called Auntie Pasta. We sold, yes, lots of fresh pasta, cut to order, or ravioli. The concept was, stop in and get all the things you need to make a quick gourmet dinner. I had no management experience whatsoever; they hired me anyway. I was “trained” by a perpetually drunk manager at the Polk Street shop, then dumped into the world of retail food service.

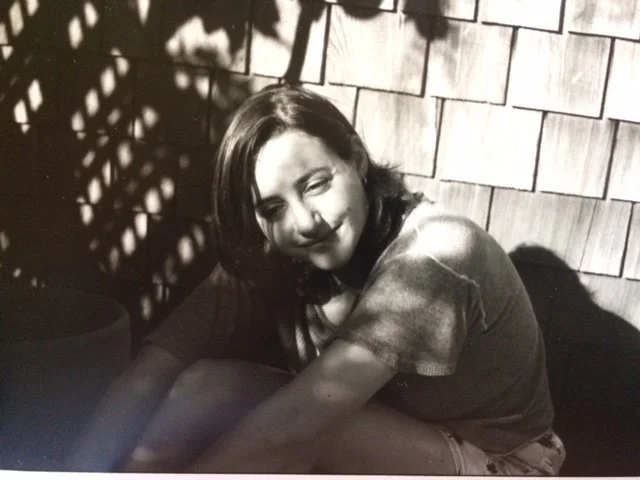

One of the other managers - the one I hoped would ask me out - soon got fired for taking the day’s profits and blowing it on blow. Another manager, Grant, asked me out and, not knowing how to say ‘no’ back then, I accepted. He did introduce me to the Red Vic movie theater, and yeast on popcorn. He also dumped me when I told him I wasn’t quite ready to sleep with him yet. Because he had goaded me to grow my hair longer, I cut it all off after we broke up and kept it in a short crop for many years.

I fell in love with my neighborhood. Noe, back then, had all sorts of cool shops. Star Magic! Three bookstores! Shoe shops and a cobbler! The little converted garage that had jewelry on paper cards tacked to the walls! Real Foods (filled with young employees who flirted with customers as they browsed the produce)! The Meat Market Cafe, its space a former meat market with hooks still hanging from the ceiling!

And I spent most evenings at the Rat and Raven. I wasn’t much of a drinker, still, and I hated beer. I would order a Sierra Nevada and take two sips, or just have sparkling water and lime if I was really broke. I went to the Rat because I had no friends; I knew nobody in my new town except the folks I worked with. There I met Jonathan Segel, a bartender who became a friend and was also, incidentally, a greatly talented violin player in Camper Van Beethoven. I met a sweet guy named Bob who sold me his cracked black leather jacket for twenty bucks; it was too big but made me feel like a badass. I also learned that meetings guys in bars was not the best way to find a boyfriend. I had a decent amount of bad sex with guys I never saw again before I figured this out.

The CEO of our small food company was a married older guy who had a reputation for partying. He took me out to dinner one night, at a sushi place on Geary, ostensibly to talk shop. Naturally, he drank a bunch of sake and then insisted we go dancing at the Brazilian place on Van Ness. When I refused to dance with him, he sulkily said he’d drive me home. As he weaved down Church Street, he plunged his hand under my shirt and bra. I froze and hugged the door. When we got to my apartment, he asked to come upstairs, and assured me we had a special connection. That connection, however, was severed not long after when he had an underling fire me from my job.

For so many years I was underemployed, broke, and still searching for myself. I wanted sex but was terrified of the AIDs crisis that I saw, heartbreakingly often, in the young frail men in the Castro. I wanted to be a poet, too; I started reading at open mikes, hands shaking the slips of paper that I held. The Chameleon, with Bucky Sinister presiding, became my Monday night haunt. He once read my scrawled name, Julie K, as Juliet, and that became my poetry name. I was fortunate to read with people like Beth Lisick and Michelle Tea and Eli Coppola. The heartache in my personal life gave me lots of fodder.

Through it all, my big sister supported me from Oakland. Until she couldn’t. Her melanoma, which had resulted in surgery years before, had metastasized to her liver. She told me, one day as I visited her at Kaiser, that she’d decided to stop the chemo. She couldn’t bear it anymore. I knew what she was saying. I just couldn’t process it; it was like hearing the sun would stop rising. I was working another crappy restaurant job when the call came to rush back to Kaiser. She died the next morning.

Who was I without her?

By then, I had friends. They moved me to a cheap studio shortly after she died. Then I met a wonderful guy who I dated for many years, the first healthy relationship of my dating life. I began to temp, and ended up with a job that paid more, as San Francisco definitely was not for broke poets even then. I spent many nights at Bottom of the Hill, the Blue Lamp, the Hotel Utah and Covered Wagon; music was a deep part of who I was.

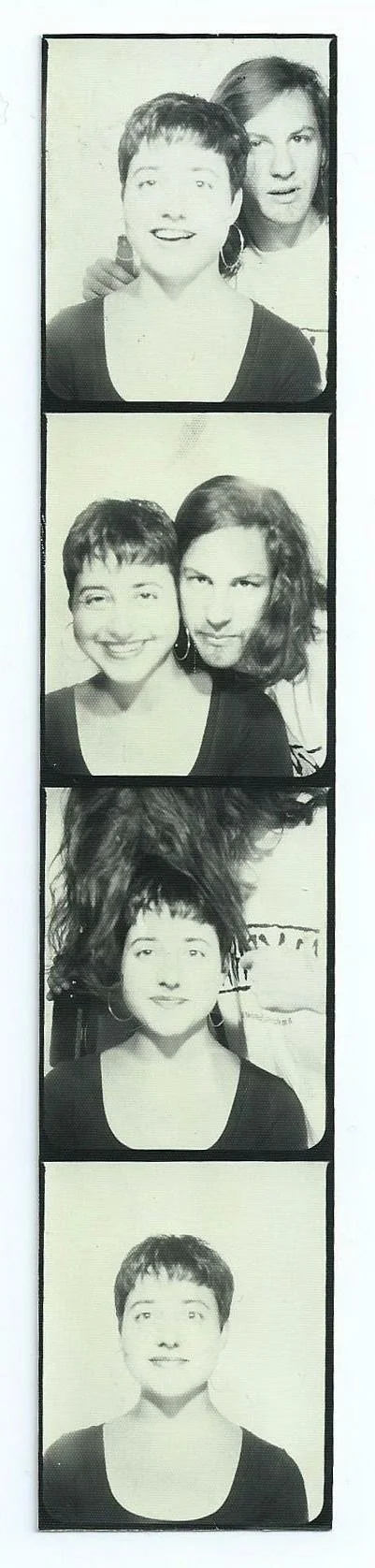

I wore vintage dresses and combat boots. I ate pancakes at Kate’s Kitchen. I dreamed of being a drummer, and still do, I waited way too long to address my depression; I made a lot of mistakes. I also got lucky enough to befriend a girl who worked in the salon where I got my short haircuts; she is still my best friend, over 30 years later.

I guess my move to a marina in Richmond was another one-way ticket. I can’t afford to move back to San Francisco, and I like the beauty out here, the quiet that’s mostly broken by waves on the shore or birdcalls. I miss the City but it hasn’t let me go. I don’t expect it ever will.

Julie Kramer is a lovely poet and friend whose cat, Shteve, should have his own social account. I Didn’t Come Here to Fight, a book of poems can be found here. For pictures of Shteve and the Richmond Harbor, follow her on Instagram @juliekramer66.